There are some bands that it’s ‘cool’ to like and some that aren’t. There is no written law to govern these things, it’s just the way it is. I’m right behind anyone who proclaims an unshakeable love for the music of Abba because, firstly, love them or not they were unquestionably one of the greatest pop bands of all time, and secondly, passion about a musical act, whoever that may be, is in itself a cool thing. But the truth is, as far as the laws of credibility are concerned, Abba will never carry the same weight as The Beatles.

In the 1980’s it was cool to like The Smiths, then again it seemed that there were more people happy to be considered uncool by dismissing the band as cardigan wearing miserabilists. In my experience fans of The Smiths were the most devoted and passionate of any band, whereas there were those that might pretend to like them even though they still secretly preferred Duran Duran. I was neither of those. I could see that there was something interesting going on, particularly with the distinctive and thematic artwork and the wit and irony of song titles like Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now and Shoplifters of The World Unite, but as was always the case, my ongoing opinion was influenced by my first impression of the music itself. The first Smiths song that I heard was What Difference Does It Make, when the band performed it on Top Of The Pops in 1984, I didn’t like it and that was that. If, on the other hand, I had seen them performing This Charming Man a few months earlier my opinion might have been completely different.

For music fans musical tastes and preferences are like a badge of honour and say something about who we are. In a literal sense you could be wearing a Clash pin badge in the hope that it might make you seem edgy or rebellious in some way but, if you don’t really like the band that much, you will soon be found out. As Alan Partridge once proved, all credibility will be lost if, when questioned by a genuine fan, you proclaim you’re favourite Beatles album to be ‘The Best of The Beatles’, which is why I have always found it both surprising and admirable that Noel Gallagher considers Never Mind The Bollocks and The Beatles red & blue compilations to be the best albums of all time.

You can’t fake these things, which is why I have never admitted to liking The Velvet Underground even though I think that I should. They are arguably the coolest of the cool, and for an alternative music fan an essential touchstone, but other than Venus In Furs, I’ve never really liked their music. Despite being an unpopular opinion I’ve always been happy to admit that the only Rolling Stones album I would ever listen to is Emotional Rescue, and it’s never bothered me that I’ve never been a big fan of The Clash.

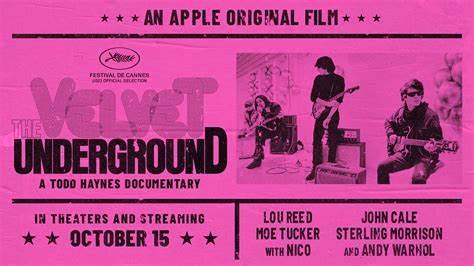

In both cases I can see the attraction and that’s enough. But it isn’t the same with The Velvet Underground. I would always admit to not really getting them, but I’ve never been comfortable with that. Everything about them suggests that I should like them; the image, the experimentation, the male-female dynamic, and most important of all, the number of bands that they have influenced whose music I love. Again, I see the attraction, and can see why they’ve been so inspirational to so many, but I’ve just never enjoyed the music, and I would have carried on living with that millstone had it not been for Todd Haynes film about the band, simply titled The Velvet Underground.

I watched the film within a few days of it’s release in October 2021 and it reminded me just how incongruous it was that not only did I not really care for them, but that I couldn’t bear to listen to the majority of their music. Although the music in the film was mostly familiar, there were several moments that provided a glint of sunlight onto my resolute determination to remain unmoved. There was Mo Tucker for one, a unique drummer, reluctant but endearing singer, a wholly likeable person and a reminder that this was a band of misfits, of disparate characters that were more than the sum of their parts: if you really didn’t like one member then there you were sure to like at least one of the rest. In John Cale there is so much to like, his talent, his Welshness, his sense of musical adventure. The baroque influence and the melodrama that he introduced to the sound was integral to it and responsible for the exceptional Venus In Furs. Sterling Morrison seemed quiet, and unique as a musician, still a key component to the sound and approach, with the fact that he deserted the music scene completely when he left the band further adding to his enigma. And then there was Nico. Her 1968 solo album The Marble Index has been a favourite of mine for many years now so are the Velvets really that different? I felt that it was now time to give them another chance.

Over the years I’ve learned that there are times when a fondness for a band will develop via an unlikely route. Genesis are a case in point, my route to liking them coming via a different band. A performance of Forgotten Sons in 1982/83 led to a brief obsession with Marillion, and when playing Script For A Jester’s Tear one day, my older brother pointed out that they sounded just like Genesis. Although I strongly disagreed with that statement – I had never liked Genesis – when he was out of the house, I began to play his Genesis LP’s, which were almost exclusively from the Peter Gabriel era. The comparison was glaringly obvious and an obsession with early Genesis was borne.

With The Smiths the route was more direct. I wasn’t particularly keen on Morrisey’s voice initially but the key to my change from ambivalence to fan came through seeing an old performance of This Charming Man on The Old Grey Whistle Test around 1986. I then borrowed a friends copy of Hatful of Hollow and played it constantly, and that’s when they clicked. I didn’t like every song, but such was the variety of their music that for every track that didn’t grab me there were two or three that would: for every What Difference Does It Make there was a Handsome Devil, Hand In Glove and This Night Has Opened My Eyes. Having had many good-humoured arguments with another friend about the merits of the band over the previous year or two she gave me a cassette copy of The Queen Is Dead and that sealed the deal. Morrisey’s lyrics, Marr’s guitar combined with the rhythm section of Rourke and Joyce made it the complete package. I may not have liked every song, but I could still listen to a whole album and before long I had grown to like Morrisey’s voice too.

And so it was with The Velvet Underground. My route in ultimately came via a recommendation for Live At Le Bataclan, the album of a reunion performance featuring Nico, John Cale and Lou Reed in 1972. Along with a few Velvets classics the album also features solo tracks from each of the three artists. Although the Nico tracks were still my favourites, I liked the rest enough to bolster my determination to finally understand what all the fuss was about and, having committed to giving the Velvets back catalogue a proper listen, I finally got it. But rather than being struck by one particular album, the epiphany came through one single track, Ocean, an outtake from the sessions for the album, Loaded. The track is a serene, tranquil oasis in the Velvets cannon, and is delivered in hushed tones by Reed. In hindsight, his voice had been the biggest barrier to my liking the band. I still wouldn’t class myself as a fan, and I still find White Light/ White Heat unlistenable, but generally I see and hear both the band and Lou Reed solo in a different light. It isn’t enough to change my life, and it won’t make me any cooler as a person, but I’m pleased that I gave them another chance, and I am happy to begin a new year by being able to say that, in all honesty, I do quite like The Velvet Underground.