Gatefold Galleries

One of the nicest things about the vinyl revival is that sleeve art is a proper size again, and it’s everywhere. It seems that wherever you go nowadays you’ll see an album cover, and not just in charity shops, but proudly displayed in frames in pubs and restaurants too. I’ve even seen a pile of records in a café, flicked through them, and asked if they were for sale only to be told that they were just for show. It isn’t as if artwork had become an afterthought exactly – there were some classic covers in the CD era – it’s just that sleeve art looks better at 12-inches square.

Record Store Day obviously played a big part in vinyl’s rise in popularity in the last couple of decades, but for me the revival became real the day I walked into a local Sainsbury’s & noticed two small shelves of LPs at the end of the milk & yoghurt aisle. To see vinyl for sale in such prosaic surroundings was both pleasing and disorientating. Records had now become a lifestyle choice, and by popping a copy of Hounds of Love into our trolley alongside a packet of Jordan’s Granola and a bottle of semi-skimmed, we were revealing something about our inner selves beyond just what we eat for breakfast.

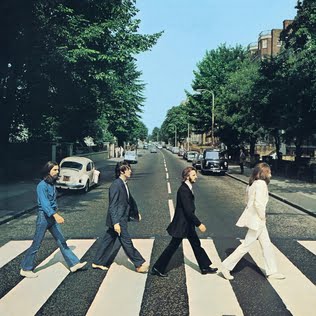

One thing that was obvious when spotting the LPs in a supermarket was that even at a distance some of the sleeves were as recognisable as a tin of Campbell’s soup or a box of Weetabix. Records had been reduced to mere products in that sense. Dark Side of The Moon, Rumours and Nevermind were instantly familiar to the point that without hearing the music you might then be accompanied on your weekly shop by a ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ or ‘Us and Them’ earworm. There are a number of sleeves that have become equally familiar on a universal scale over the years. They would include Ramones debut, London Calling by The Clash, The Velvet Underground & Nico, Abbey Road, Aladdin Sane and Unknown Pleasures. All simple but striking images that linger in the mind.

However strong those images are though, their simplicity doesn’t necessarily make for the most interesting album sleeve, in the same way that the Mona Lisa isn’t even the best painting in the room it’s hung in, let alone the world in general. Ziggy Stardust would probably be a lot of people’s favourite Bowie sleeve, but it’s complex so not as easy to remember as the simpler portraits like Aladdin Sane or Low. Likewise, Sgt Pepper is known by everyone but isn’t as easy to mimic as Abbey Road.

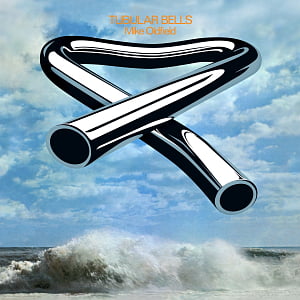

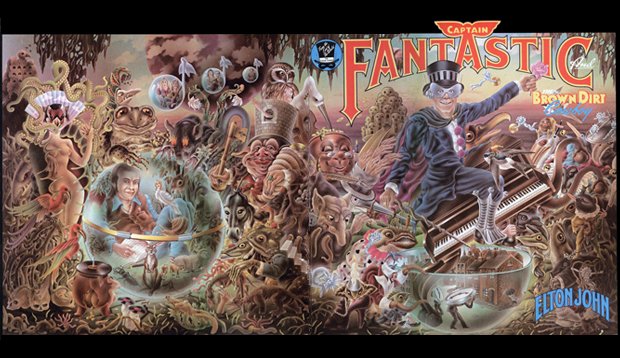

Two album sleeves that I was fascinated by as a toddler were Tubular Bells and Elton John’s ‘Captain Fantastic & The Brown Dirt Cowboy’. Seeing the Tubular Bells sleeve is one of the first ‘musical’ memories I have. I didn’t know that surreal was a word then but it was that element of the image that intrigued me – what was a piece of twisted pipe doing in the sky? Why and how was it just hanging there, above the sea? Mind blown. Captain Fantastic was no less surreal, but there was a lot more going on. It was complex and multi-layered, a classic gatefold sleeve of the time – the front & rear forming halves of one bigger image that seemed to reveal something new every time you looked at it. And, of course, at the age of 5 I thought the pooping pot was hilarious.

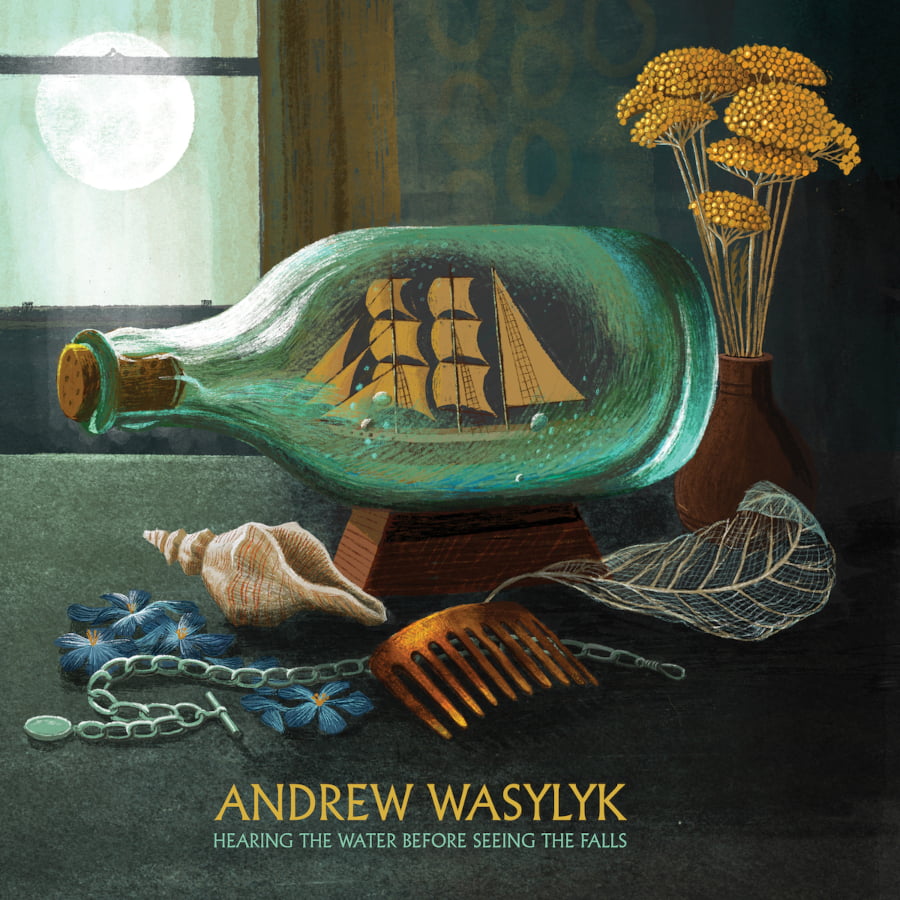

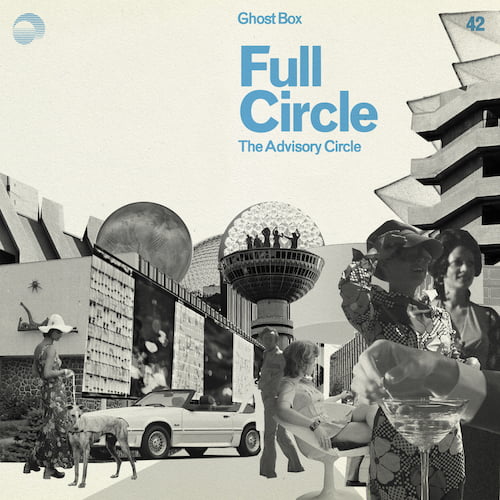

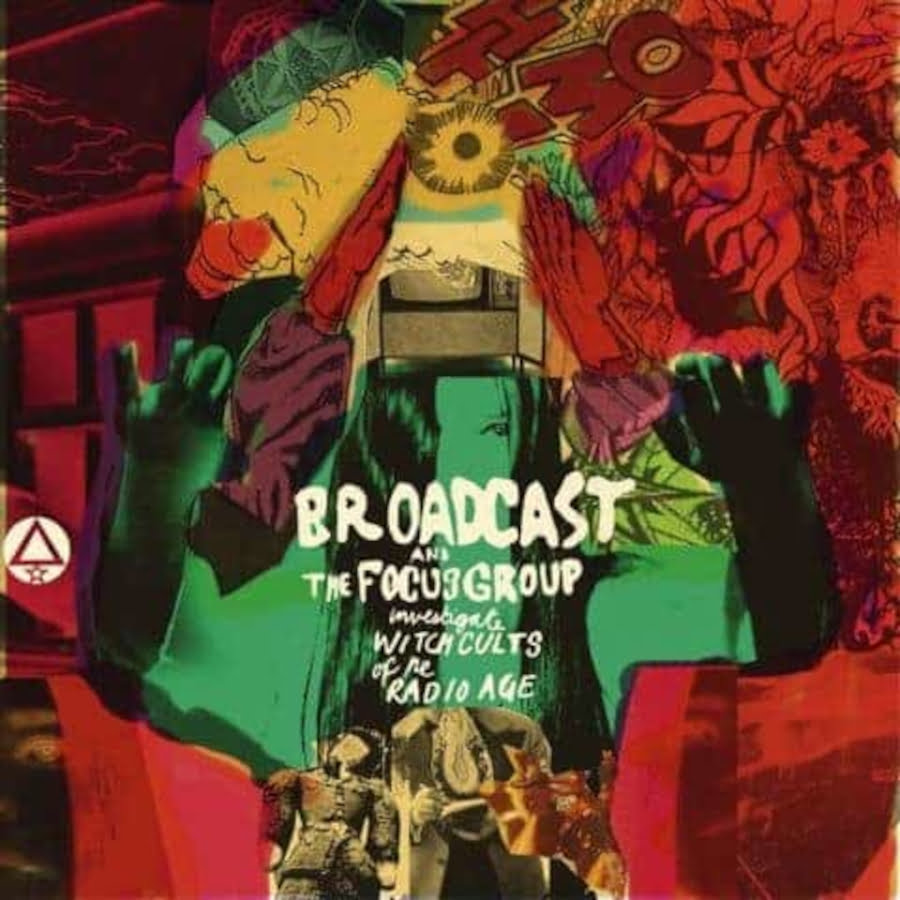

But anyway, to cut a long blog post short, the return of vinyl means that there is fantastic new artwork to enjoy, and a lot of it. With luxurious new pressings comes not just luxurious sleeve art but also postcards, photo books & fold-out posters. Even the vinyl itself is an artform at times. When you spend your hard-earned money on a new release now, you’re not just getting something to listen to, you’re getting an art gallery. Two great examples of art and music colliding in this way can be seen in the output of Ghost Box Records and Clay Pipe Music. The releases of both labels feature the designs of their founders. In the case of Ghost Box, founder and graphic designer Julian House has created a wholly distinctive style that is immediately recognisable as both his and that of Ghost Box. His cut-up, collaged imagery suits the hauntological nature of the music perfectly, that of fragmented memories and dream-like tones. Clay Pipe founder Frances Castle, a professional artist and designer before she became a label owner, designs most of the sleeves, and they are works of art in every sense – colourful, evocative images that would be equally at home on a record sleeve or in a major gallery. And as with the work of Julian House & Ghost Box, the artwork is the ideal accompaniment for the serene, often bucolic nature of the music within.

Record shops themselves are like alternative art galleries. I know I’m not alone in having spent hours in my younger days flicking through the racks even when I knew I didn’t have the money to buy anything. It was partly to see what was out there to go back & buy at a later date, but equally just to enjoy the artwork. I don’t even think it too strange that some people buy LPs just so they can stick the sleeve in a frame and hang it in their living room or on their landing, never to hear the record itself. It’s a shame not to listen to the music, but it just goes to show that a vinyl record isn’t a mere consumable product. The definition of what actually constitutes art may have broadened over the years – The Velvets & Nico sleeve was just an Andy Warhol banana after all – but surely we’re not living in a world where someone would buy a box of Weetabix, discard the contents & hang the box above the mantel piece yet. Are we?